Varied responses to a low-protein diet in diverse groups of mice highlight need to examine personalized “food as medicine”

A protein-restricted diet has different metabolic effects in mice with different genetic backgrounds and between male and female mice, highlighting the importance for personalized medicine, as well as personalized “food as medicine”. ![]()

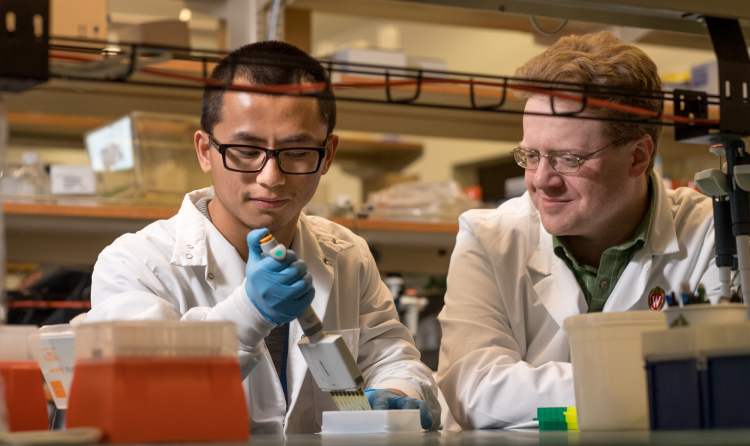

This was found in a new study from Dudley Lamming, PhD, associate professor, Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, and Cara Green, PhD, research associate, Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism (pictured right), published in Cell Metabolism. Lamming and colleagues measured how protein restriction impacted body weight, energy expenditure and glucose tolerance in mice.

Despite evidence that genetic background and sex are key factors in the response to diet, most protein intake studies examine only a single strain and sex of mice. This study, however, sought to understand the effect of varying protein consumption in genetically diverse male and female mice.

To do so, the researchers fed the mice one of three diets with the same number of calories, but varying levels of protein.

“We are interested in how genetic background and sex impact the way we respond to different nutritional interventions, so we can determine how every individual can best improve their health using food as medicine,” Green says.

They found that in two of the three strains, male mice had a stronger beneficial metabolic response to a low protein diet than in the female mice. Male mice in these strains also had a greater improvement in glucose tolerance than their female counterparts. Interestingly, one of the strains was almost completely metabolically non-responsive to changes in protein intake.

While the significance of the metabolic health improvement varied between the strains, with age, and between male and female mice, the evidence suggests that despite the genetic variation between these strains of mice, reducing dietary protein intake has many broadly conserved positive effects on the metabolic health of mice – just as it does in humans.

This confirms and extends similar findings from Lamming’s group showing that restriction of protein improves metabolic health and extends the lifespan of one commonly used sex and strain of mice, and a randomized clinical trial that showed that overweight adult males lost fat mass and had decreased blood sugar when eating a low protein diet.

“Consuming less protein may be an easy and translatable way to promote and restore metabolic health, even when started later in life,” Lamming says.

Banner: Dr. Lamming works with co-author Deyang Yu, PhD, in his lab. Credit: Clint Thayer/Department of Medicine